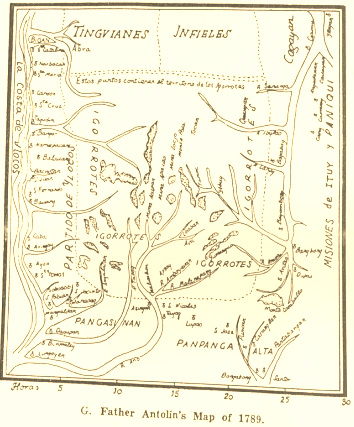

In the beginning, long before the coming of the Spanish missionaries and soldiers to pacify and conquer the pristine Upper Agno Valley and the Tierras de Montaños of Northern Luzon at the latter part of the 16th Century, native villages has been in dotted existence within the breadth of what to become the territory and geopolitical entity known today as the town of San Nicolas.

As early as the second decade of the 17th Century, Spanish Missionaries and Historians had already been mentioning in their chronicles, localities which can be considered as the mother places that had spawned today’s town of San Nicolas.

Villages such as the Ambayabang(Balungao) of the legendary native chief Cayon Dagarag, Maliongliong (Mallilion) that later housed the dominican mission of San Josef in 1732, as well as that of Apsay (Agpay) of the present Agpay Eco-tourist fame, can already be found in the old maps, some dating as far back as the year 1625.

The gradual development of the said villages, as they later opened to Spanish interactions and incursions, especially of Ambayabang and Maliongliong, were the intertwined genes that had formed the nucleus of the town.

It was mainly the establishment of religious missions that had paved the road towards the founding of San Nicolas as a town.

The alternating missionary activities of the Dominicans and Augustinians in the area, beginning in the year 1607, engendered two major missionary routes to the genesis and evolution of the town of San Nicolas, from an informal mission community of the early Spanish period to an independent and vibrant pueblo nuevo of the 19th century Pangasinan.

First of the two routes mentioned earlier that led to the founding of the town was one that came from the Dominican central Pangasinan towards the northeastern part of the province through the establishment in 1732 of the San Josef Mission in Maliongliong (Mallilion).

The other route was one that came from the southeastern Augustinian mission areas embarking from Ytuy and Baler of the Pampanga delta and Sierra Madre region through the San Nicolas de Tolentino Mission in the village of Ambayabang (Balungao), founded by a very young Augustinian friar named Agustin Barriocanal sometime in the late 1738 to early 1740s.

In due course of times and events, the two paths eventually met and from that point was born a town with a history to etch in the unadulterated pages of fate and destiny.

THE ILOCANO EXODUS

The latter part of the eighteenth century and the onset of the nineteenth century, saw the diasporic migration and resettling of Ilocano families to Pangasinan.

Rapid population growth and the scarcity of land for habitation and tillage, drove the industrious and persevering Ilocanos to migrate and leave their lands.

Searching for the proverbial greener pasture, many of them found their way to the eastern and western parts of Pangasinan. Those who opted to settle in the east were initially confined to the towns north of San Fabian.

Later, they went farther eastward as they found the rich natural resources of the frontier region such as gold along the Agno River, timber and wood from the lowland plains, and dense and lush green forest which they later cleared and converted into vast tract of arable lands they made good use for plant and crop cultivation.

Ilocano migrations to the area may have started between the period from the first decade to middle part of the 18th Century. Although, those were so insignificant that it went unrecorded in the towns historical anals and chronicles.

More batch of migrant Ilocanos found their way into the vicinity of the town in the year 1780, but, the migration that inked the indelible mark in the town’s recorded history occurred in the year 1800.

The 1800 influx was a highlight batch as it was by far the largest contingent that came into the area. It include among others the couples Nicolas Patrico and Isidra Sangalang, and the families of Jose Castillo, Raymundo Umaguing, Bernardo Alimorong, and the company of other families and individuals.

The group came from the towns of San Fabian and San Jacinto, two among the first towns to be established in Pangasinan. Originally, they came from the Ilocos before they migrated to Pangasinan.

When the group arrived in the area , they searched for the most conducive place to establish their settlement. And it did not took them long to find the proverbial spot in the southern flank of Rio Ambayabang near the immediate vicinity of the then humble mission settlement of San Nicolas de Tolentino that had relocated there from its former base in the village of Balungao.

The place was strategically resting on a high ground that made it safe from the perennial flooding of the Ambayabang. There had also been erected a modest chapel by the San Nicolas mission nearby, which had made the place even more appealing and desirable to the emigrants.

As there were only few inhabitants in the place before their arrival, converts from Balungao and those from Maliongliong and other settlements within the radius where the mission’s chuch bell can be heard, would go to the place and join in fulfilling religious obligations expected of zealous catholic faithful.

Thus when Nicolas Patricio’s group arrived in the area, the place formally became a barrio as their number supplied enough quantity of people required and the stability needed to formalized the mission’s relocation site as an organize civilian settlement.

The newly formed community became the core that created the foundation of the future poblacion. This could be the basis upon which the long-believed oral history attributing the origin and founding of the town to Don Nicolas Patricio y Mejia came from.

However, in the light of the facts having drawn and found from all available sources, the Nicolas Patricio story is hereby taken just as a part of the whole historical tableau of San Nicolas history and not as the be-all-and-end-all sort of thing.

Throughout the span of the 19th century, Ilocano migration flowed-in continually. More communities rose within the area. And before the elevation of San Nicolas to a pueblo visita, two new barrios were born, San Rafael and San Jose, both a product of Ilocano migration. In 1810, by the instigation of local and church leaders particularly that of San Nicolas mission, the principales and other eminent personalities of the existing settlements then decided and initiated procedures for the formalization and official establishment of San Nicolas mission to a pueblo visita, concurrent to becoming a pueblo civil.

This was to be effected and carried through the union of all the existing villages in the area under one organic entity.

San Nicolas mission becoming a pueblo visita and a pueblo civil means, it was to become civilly independent but still ecclesiastically subordinated to a mother parish.

By civil authority, it became a part of the Commandancia Politico Militar de Nueva Ecija. Ecclesiastically, it became a matrix of the pueblo parroco de Tayug under the jurisdiction of the Augustinian Prelate Provincial based in Pampanga.

The most significant factor brought by the elevation of San Nicolas from a mission to a visita and a pueblo civil was the advent of civil government in the town. Becoming a pueblo civil entailed the appointment of a governadorcillo to oversee the administration of the pueblo’s civil affairs.

Governadorcillos were next in rank, prestige and power after the Cura Parroco in every Spanish controlled part of the Philippines during those periods. Their main function was to collect tribute from among the natives aged nineteen to sixty.

Every Governadorcillo ascends to office by direct selection and appointment, and later, by the endorsement of the local parish priest.

From the information kept in the file of the late Don Juan C. Rollolazo, who served as Vice Mayor from 1938 to 1940, it was Don Bernardo Alimorong who was appointed as the first governadorcillo of the town of San Nicolas in its elevation from just a mere mission settlement to a pueblo visita and pueblo civil in the year 1810.

Such made him, the first in the roster of governadorcillos of the town, on the basis of San Nicolas under the Commandancia of Nueva Ecija. As governadorcillos during those times were to serve only for a year, succeeding personalities who likewise served by appointment in the same capacity and office before 1818 were:

1811 – Don Pascual Verceles

1812 – Don Juan Castillo

1813 – Don Mateo Macairap

1814 – Don Martin Castillo

1815 – Don Bernardo Bonifacio

1816 – Don Juan Basilio

1817 – Don Vicente Erese

Simultaneous to the processes undertaken in the elevation of the mission to a visita and the formation of the pueblo civil, was the choice of the site that would fit the requirements for the new town’s poblacion.

The most important factor among other considerations was to ensure that the church building was built and located on higher ground to remove it from direct threat of flood and that together with the town plaza it ought to be at the heart of the town. From this center, the streets should radiate out to the outlying barrios.

The Nicolas Patricio-led Ilocano settlement that had absorbed itself to the San Nicolas mission community inevitably became the pueblo nuevo’s poblacion. The social infrastructures existing in the place such as the Catholic church edifice, though a modest one, made it almost automatically the preferred if not the sole fitting candidate for a place of the poblacion.

Furthermore, the site was proximate to the next Augustinian parish of Tayug. In fact, as early as 1760, San Nicolas Mission Settlement, although still a sparsely populated mission community, had been considered to be at par with modern communities during those periods.

Having been chosen as the site of the pueblo centro or poblacion, the Ilocano village of the relocated mission of San Nicolas had the privilege to adopt and maintain the mission and locality name the same as the new pueblo’s official name.

From that period on, San Nicolas was the title use to refer to the entire territory in which the existing settlements then had integrated to form a pueblo civil and a pueblo visita, though, still dependent as matrix of pueblo parroco de Tayug.

The former Barrio San Nicolas became the town center or Poblacion with Nicolas Patricio as its first Cabeza de Barangay.

With the founding of the pueblo visita, prominent families rose to further eminence and eventually evolved to become the town’s “nababaknang” or principalia class. From them rose and borne the future ruling elites of the town.

These principalia families can be easily recognized by the place of their residences as they usually stands near the town center, thus, near the church building, the tribunal, and other government buildings. The nearer a house to the plaza centro, the more important and socially higher class a family was.

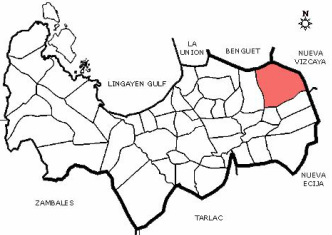

On May 3, 1817, San Nicolas was ceded to the civil jurisdiction of Pangasinan from the Commandancia Politico Militar de Nueva Ecija under the province of Pampanga. This transfer ushered-in a new system through which civil officials of the town were installed to office commencing the year 1818.

Previously, all governadorcillos were installed to office by the sole and direct appointment of the Cura Parroco. However, in 1818, barely a year of being a town under the province of Pangasinan, the appointment of governadorcillos were given a dash of democratic elements as San Nicolas made its historical first exercise of electing its town officials through a local electoral body composed of twelve members selected from the principales of the town.

These principales were men of high stature and regard in the community. Usually, they were from the roster of previous gobernadorcillos and cabezas de barangay who served in the town.

Selected by means of draw lots, leaders representing the various villages in the town then gathered and convened the electoral body, and for the first time elected the governadorcillo.

Don Nicolas Patricio y Mejia, a prominent and respected Ilocano leader, won the body’s favor and thus became the first to be installed to the office of governadorcillo by means of an election. His election was later confirmed by the endorsement of the Cura Parroco.

He was the first to serve as Governadorcillo with the pueblo as part already of the province of Pangasinan. All his predecessors had served their terms as governadorcillo with the town still under the jurisdiction of Nueva Ecija. Don Nicolas’ term was marked by so much gain of progress and stability as unity and bond among the town’s ethnic population of Pangasinensis, Ilocanos and the Igorots, were forged and nurtured by his dynamic leadership.

His administration brought so much accomplishments and development to the town that his remarkable performance became his successor’s benchmark in their administrations.

Continuing the exemplary model of public and government service he rendered had ensured sustained progress and development to the town. By the close of 1845, it already had a casa real (state house), a school house and an accumulated value of 720 tributes sufficient enough to support the maintenance of a local cura parroco (as they were at that time still under the patronage of the Cura of Tayug).

It was also highly possible during that time that the modest Catholic chapel they used to have, had likewise grown into a bigger and larger edifice with its own parish house or convento. These and the latter mentioned elements qualified the town for elevation to another social organizational level from a pueblo visita to a full-pledge pueblo parroco

THE ROYAL DECREE OF 1846

After having gained remarkable achievements in the financial and infrastructural aspects of development, San Nicolas applied for the elevation of its status from a pueblo visita to a pueblo parroco in the year 1845. Leading the petition was the town’s governadorcillo himself, Don Domingo Basilio.

The draft of the petition was submitted for approval to the insular government in Manila. It executed the formal promulgation of the town to a separate and independent Catholic Parish. After favorably endorsed by the Alcalde Mayor (provincial governor) and made recommending approval by the bishop of Nueva Segovia, finance officials in the superior Government in Manila found the petition meritorious.

On June 18, 1846, Governor General Narciso Claveria y Zaldua issued the Royal Decree granting the spiritual separation of San Nicolas from its mother parish of Tayug.

The Spanish Royal Decree bore the ecclesiastical credence that sealed the formal elevation of San Nicolas as a pueblo parroco and by indirect effect, solidified its status as a pueblo civil. Don Mateo Miranda was the incumbent governadorcillo when the decreto real was granted. P. Jose Manso was the first curate assigned by the Dominican Province to administer the newly-elevated catholic community.

Yet, while its formal recognition as an independent town and parish had ended its being just a matrix of another territory by catholic ecclesiastical parlance, its being subjected to jurisdictional seesaw from one civil province to another had unfortunately lingered.

On November 15, 1851, San Nicolas, together with the town of Tayug were again separated from Pangasinan and re-incorporated to the province of Nueva Ecija. There was a plan then by the Spanish central government in Manila to create a province out of the northwestern part of Nueva Ecija, together with parts of Pampanga and Pangasinan.

The proposed new province, with envisioned capital at Rosales (Pangasinan), was supposed to be called Nueva Cuenca, which among others were to include the towns of Paniqui, Barug (now Gerona), Cuyapo, Guimba, Muñoz, San Jose, Puncan, Lugsit (Lagasit?), Rosales, Umingan, and Tayug.

San Nicolas was by technicality included on the basis of its former relation to Tayug as an ecclesiastical matrix and likewise its being an Augustinian parish.

Fortunately, the plan for Nueva Cuenca would later be abandoned and would never materialize. In lieu of it was the creation instead of the Commandancia Politico-Militar de Tarlac in 1860 covering the Kapampangan towns of Bamban, Capas, Concepcion, Victoria, Tarlac, Mabalacat, Magalang, Porac and Floridablanca.

In 1873 the last four towns mentioned were returned to Pampanga, and in 1875, with the five remaining unreturned towns together with the towns of Paniqui, Camiling, Moncada and Gerona from the province of Pangasinan, Tarlac was made into a separate alcaldia or province. Cuyapo, Guimba, Muñoz, San Jose, Puncan, Lugsit (Lagasit), Rosales, Umingan, Tayug, and San Nicolas would on the other hand remain as part of the province of Nueva Ecija.

In April 16, 1863, a petition requesting for the return of the towns of San Nicolas and Tayug to the civil jurisdiction of Pangasinan was sent to the Superior Government in Manila.

Gobernadorcillos Don Raymundo Sumaguing of San Nicolas and Don Julio de Tolosa of Tayug, were the main proponents of the petition.

As recorded in the entry pages for 1861 to 1863 in the Bureau of Records Management of the National Library, the document detailed it as thus,

“Un solicitud delos Gobernadorcillos y Principales de los pueblos de San Nicolas y Tayug, provincia de Nueva Ecija, pidiendo a separarse de la expresada y agregarse a la provincia de Pangasinan …”

On May 16, 1863, the petition was officially granted, finally placing the town of San Nicolas permanently a part of the province of Pangasinan and consequently as its north-easternmost town.

On the other hand, it was not until 1902 upon American implementation of the local civil government reorganization as mandated by the Philippine Commission that the towns of Rosales and Umingan were ceded to the province of Pangasinan.

The towns of Natividad, San Quintin, and Sta. Maria were all previously part of either the town of San Nicolas or Tayug. Most part of Natividad were taken from the territory of San Nicolas such as that of San Eugenio, Licud, Recodo, Barangobong, Amanit, San Modesto and a large part of Barangay San Jose.

Remaining portion of the latter remained as part of the town of San Nicolas with a status of a full pledge barangay. Likewise, some territories such as those located near today’s Barangay Legaspi were later lost and ceded to its neighbor and previous ecclesiastical mother town, Tayug.

In the later part of nineteenth and early periods of 20th century, successive natural and biological calamities tested the town and its people.

In 1837, an earthquake rocked the town. A fire broke out in 1864 that consumed the whole town including the town’s church and its convent to the ground. Another church was built in place of the burnt edifice and was made out of wood and base of ladrillos (bricks) with iron sheets roof.

A convent was constructed later which were made of stone masonry. But all these structures together with the schoolhouse and tribunal were again burned down in the Fil-American war of 1899.

Famine gripped in 1872 and by the turn of the 20th century, Cholera epidemic strikes, in 1901 and 1902; Plague of small fox in 1905; havoc of influenza in 1918 and 1919 and the most devastating flood in 1935.

Despite all these odds, the founding townspeople pioneering spirit never waned. They stood-up more resolved in every fall, and with their remarkable fortitude and determination, their endurance paid the laurel leaf as the town they painstakingly nurtured and cared for, had seen itself winning all the battles it had fought and came-out a victorious and ultimate survivor in its walk through various periods and times.

Sources:

Sherwin Bartolome Soria

http://snml.weebly.com/municipality-of-san-nicolas-history.html

A Pangasinan Folio’70 : a historical document

2007 San Nicolas Town Fiesta Souvenir Program

2005 San Nicolas Town Fiesta Souvenir Program

1968 San Nicolas Town Fiesta 1968 Souvenir Program